An afferent pupillary defect (APD), also called a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), is an abnormal response of the pupil to light, indicating a problem in the visual pathway from the retina to the midbrain. It’s a key clinical sign in neurology and ophthalmology, often pointing to optic nerve or severe retinal issues. Here’s a concise breakdown:

What It Is

APD occurs when one eye’s afferent pathway (retina → optic nerve → brain) is damaged, causing unequal light response between the eyes.

The pupils may appear normal in size, but their reaction to light reveals the defect.

It’s “relative” because it’s detected by comparing the two eyes’ responses, not by one pupil failing entirely.

Causes

Optic nerve damage:

Optic neuritis (e.g., from multiple sclerosis).

Optic nerve ischemia (e.g., anterior ischemic optic neuropathy).

Glaucoma (severe, asymmetric cases).

Optic nerve compression (tumors, aneurysms).

Trauma or optic atrophy.

Retinal disease:

Severe retinal detachment.

Central retinal artery/vein occlusion.

Advanced macular degeneration (if asymmetric).

Other:

Severe amblyopia (rare).

Large unilateral cataracts (very rare, as lens opacity doesn’t typically block enough light).

Note: APD is not caused by cranial nerve III palsy alone unless optic nerve damage coexists, as CN III controls efferent (motor) pupil response, not afferent (sensory) input.

Symptoms

Often asymptomatic for the pupil defect itself—patients don’t “feel” an APD.

May have associated vision loss, blurriness, or dimness in the affected eye, depending on the cause.

In subtle cases, patients might notice colors seem less vivid in one eye.

Diagnosis: Swinging Flashlight Test

How it works:

A bright light is shone into one eye, then quickly swung to the other, alternating every 2–3 seconds.

Normally, both pupils constrict equally when light hits either eye (direct and consensual response).

In APD, the affected eye’s pupil dilates (or constricts less) when light is shone into it, because the brain perceives less light input from that eye.

Key sign: Paradoxical dilation of both pupils when light swings to the affected eye.

Grading:

Mild: Slight dilation or sluggish response.

Severe: Obvious dilation on light exposure.

Tools: Penlight and neutral-density filters (to quantify severity in subtle cases).

Clinical Implications

Unilateral APD: Points to optic nerve or severe retinal pathology in one eye.

Bilateral APD: Rare, suggests severe bilateral optic nerve/retinal damage (e.g., advanced glaucoma or bilateral optic atrophy).

No APD in CN III palsy alone: If pupils are unequal (anisocoria) due to CN III palsy, an APD won’t occur unless the optic nerve is also compromised. For example, a compressive CN III lesion (e.g., aneurysm) might cause pupil dilation but not APD unless it also presses on the optic nerve.

Workup

History: Vision changes, eye pain, trauma, or neurological symptoms (e.g., headache, weakness)?

Exam:

Visual acuity, color vision (often impaired in optic nerve issues).

Fundoscopy for retinal or optic disc abnormalities (e.g., pale disc in atrophy, swollen disc in optic neuritis).

Eye movement and eyelid check (to rule out CN III or other cranial nerve involvement).

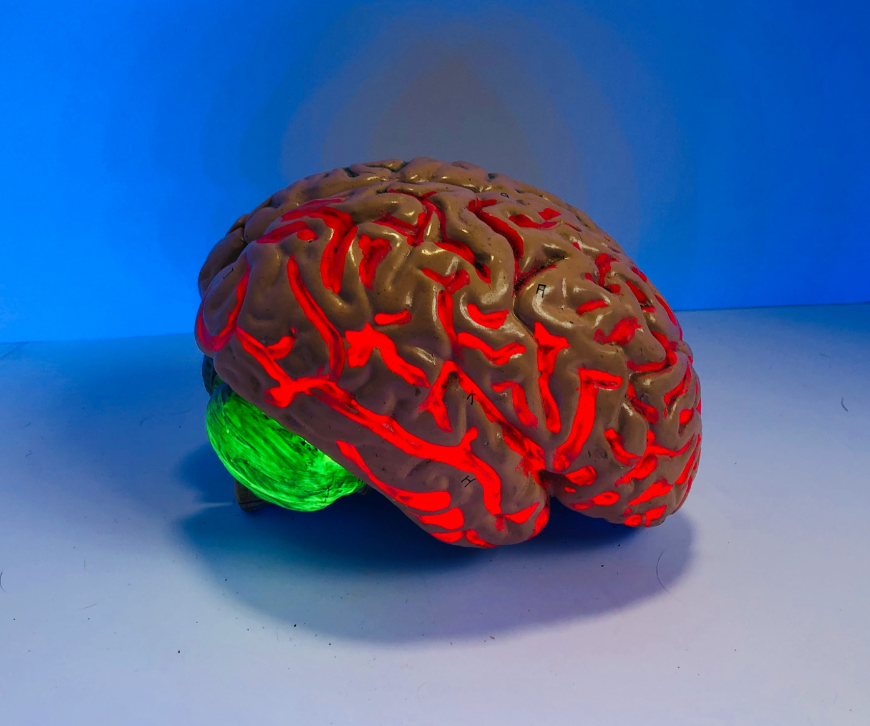

Imaging:

MRI brain/orbits if optic neuritis, tumor, or stroke suspected.

CT/CTA for trauma or vascular causes.

Other tests:

Visual field testing (e.g., for glaucoma or optic nerve compression).

OCT (optical coherence tomography) for retinal or optic nerve layer thinning.

Leave a Reply