Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are autoimmune disorders that often occur together, sharing some clinical and serological features, but they are distinct conditions with unique characteristics. Below is a concise explanation of their relationship and key points:

Relationship Between APS and SLE

- Overlap: APS can occur as a primary condition (PAPS, without another autoimmune disease) or secondary to another condition, most commonly SLE. Approximately 20–40% of SLE patients test positive for antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and 50–70% of these may develop APS over 20 years. Conversely, about 36% of APS patients have SLE.

- Shared Features: Both are autoimmune, involve autoantibodies, and increase the risk of cardiovascular and thrombotic events. Patients with both conditions may experience worse outcomes, including higher organ damage and mortality.

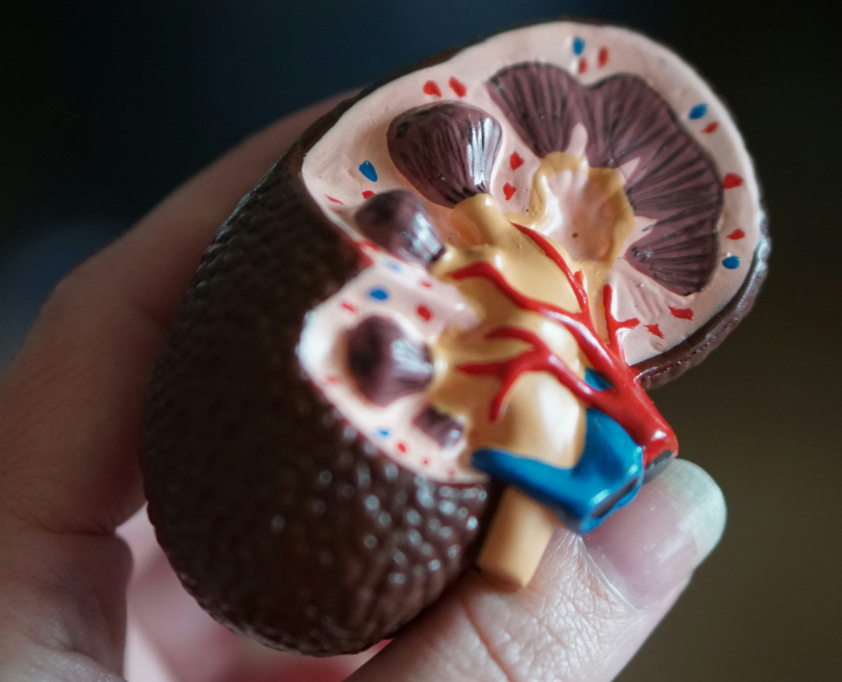

- Distinct Pathogenesis: SLE involves a broad range of autoantibodies (e.g., antinuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA) and inflammatory mechanisms affecting multiple organs, while APS is primarily driven by aPL (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti-β2-glycoprotein-I) causing thrombosis and pregnancy complications. Renal involvement in APS is marked by thrombotic vasculopathy, whereas SLE features inflammatory lupus nephritis.

Key Clinical Points

- APS Manifestations: Recurrent venous/arterial thrombosis, pregnancy morbidity (miscarriages, preterm birth), and occasionally catastrophic APS (CAPS), a rare, life-threatening form with multiorgan thrombosis.

- SLE Manifestations: Fatigue, joint pain, rashes (e.g., malar rash), renal, cardiac, and neurological involvement, with flares and remissions.

- Impact of APS on SLE: In SLE patients, aPL positivity is associated with increased thrombosis, pregnancy loss, valve disease, pulmonary hypertension, livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and cognitive impairment.

Diagnosis

- APS: Requires at least one clinical event (thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and persistent aPL positivity (tested twice, at least 12 weeks apart).

- SLE: Diagnosed based on clinical symptoms, physical examination, and lab findings (e.g., antinuclear antibodies, low complement). No single test confirms SLE.

- Testing in Overlap: SLE patients with unexpected clots, recurrent pregnancy loss, or specific symptoms (e.g., livedo reticularis) should be tested for aPL.

Management

- SLE: Treatment varies by organ involvement, using anti-inflammatories, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate), or biologics (e.g., belimumab).

- APS: Focuses on anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin, heparin) to prevent thrombosis. Low-dose aspirin (LDA) may be used for primary prophylaxis in high-risk aPL-positive SLE patients, though evidence is mixed.

- Combined Management: In SLE with APS, hydroxychloroquine reduces thrombotic risk, and modifiable risk factors (e.g., smoking, hypertension) must be controlled. Warfarin is preferred over direct oral anticoagulants for secondary prevention in APS, especially in arterial thrombosis or triple-positive aPL cases.

Prognosis

- SLE with APS increases the risk of irreversible organ damage and reduces survival compared to SLE alone.

- Early diagnosis and tailored treatment (e.g., anticoagulation, SLE flare control) improve outcomes.

Research and Future Directions

- Ongoing studies explore genetic links, immune mechanisms, and novel antithrombotic therapies to better distinguish PAPS evolving into SLE and optimize management.

- Bibliometric analyses highlight research trends in immune mechanisms, thrombosis management, and pregnancy complications.

Always consult a healthcare provider for personalized advice.

Disclaimer: owerl is not a doctor; please consult one. Don’t share information that can identify you.

Leave a Reply